Words by Joseph Moore

Photos by Kaylee Everly

Ultimo Gomez Cueba stands facing the tomb, one hand placed on top of the rectangular six feet by three feet structure, the other resting at his side. Gone is the wide, toothless smile that once seemed a permanent fixture on his weathered face. For several moments, he contemplates the words engraved in the stone. He stoops to remove clumps of weeds growing around the burial chamber before continuing down the narrow, rocky path.

The public cemetery in Cristo Rey, Santo Domingo, is a byzantine labyrinth of decaying concrete tagged with graffiti and overgrown with weeds. It’s easy for visitors to get lost in this miniature city of tombs, separated in places by only a few feet, in others by a few inches, but Ultimo has become adept at navigating the narrow alleyways between chambers. He has been carrying tools and bags of cement from one area to another for the last 16 years.

He builds tombs for the newly departed, as well as those preparing for the inevitable. Five or six times a week he performs exhumations. He chisels away the face of a tomb, collects the bones of the deceased into a plastic bag and burns the clothing. This is done to make room for the incoming casket of a wife, a brother, a distant cousin or a perfect stranger.

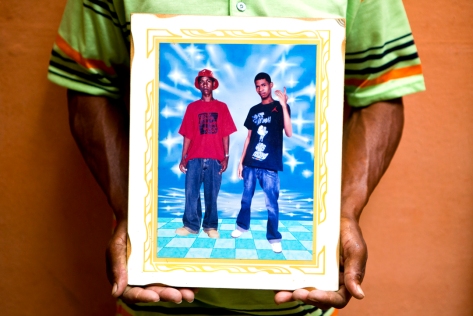

Moving from one task to the next, Ultimo does not stop to read the names of the dead engraved in the tombs, with one exception. In a secluded area of the cemetery, far from the entrance where the gravediggers await the arrival of the dead, there is a tomb that gives Ultimo pause whenever he passes. Two nameplates, one on top of the other, read “Wilfrin Antonio Gomez Gomez, 30-6-1983 to 30-5-2009” and “Eddy Junior Gomez Gomez, 30-1-1992 to 30-5-2009.”

This tomb contains Ultimo’s sons, murdered on the same day.

Twenty-five-year-old Wilfrin Gomez was an officer in the Dominican National Police. In 2009, he was given a transfer order to a new district – a promotion. To celebrate the occasion, Wilfrin went with friends to a pool hall to have some drinks. While there, one of his friends got into an argument with another group of men. The argument escalated and someone drew a 9mm pistol, shooting Wilfrin’s friend in the leg. After rushing his bleeding friend to the hospital, Wilfrin returned to the pool hall to confront the gunman. He was shot twice in the head.

That night, Wilfrin’s younger brother, 17-year-old Eddy Junior, received a phone call from the bar warning him that his brother was in trouble. He arrived at the pool hall in time to lift his brother’s lifeless body into his arms, turn toward the door and receive eight bullets in the back.

Nearly five years later, Ultimo does not get emotional when he tells this story. In a solemn, reflective tone he recounts the events of May 30, 2009. This is a stark contrast from the man who drinks beer at work and laughs with the other gravediggers as they wait for a hearse or an ambulance to drive through the cemetery’s gates, guaranteeing them some work for the day and some pesos to bring home to their families.

Earlier in the day, Ultimo supervised the burial of 56-year-old Marcelo Pena, who died of a brain hemorrhage. When members of Marcelo’s family complained that another laborer was not using enough cement to construct the tomb’s wall, Ultimo stepped in to ease the tension. He spoke loudly in rapid Spanish, gesturing wildly with his hands, his smile wider than ever.

Some of the family members accused Ultimo of being drunk and warned him that he too could end up in a tomb. Addressing the crowd in a loud voice, his smile undiminished, he reminded them all that his name is Ultimo – “final” – and he will be the last one to die.

One thought on “The last to die”