Photos and words by Shelby Wolfe

The first thing that strikes you about Bernadette Pierre is the way she bundles her long skirt together when she walks, tiptoeing around her own family members to avoid drawing attention. She glances at her husband and kids, smiles sweetly and looks away. She spends most of her day in her small, crowded kitchen mashing plantains and cooking rice. She serves her family first and takes whatever is left for herself, sometimes only a fourth of the first three portions.

Even though she hasn’t felt accepted since she decided to come to the Dominican Republic, taking care of her family and members of the community comes first.

This is a story about a family that is both Dominican and Haitian in a country that says, officially, you can’t be both. They live on a bateye, a community where generations of Haitians were housed to provide cheap labor in the sugar cane plantations. The family members own their land now but they are still poor subsistence farmers. Both parents want a better life for the children but the new law denying Haitians citizenship threatens their ability to break the cycle of rural poverty by denying the children access to higher education. However, the family still has faith that somehow their lives can change for the better.

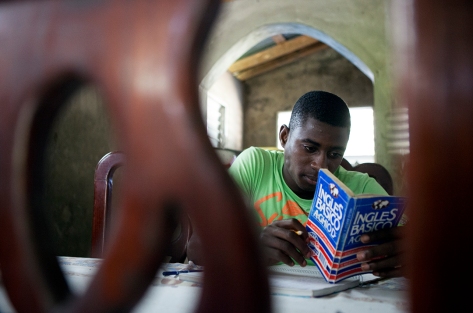

David is the youngest son and was born and raised in the Dominican Republic. Most days he walks 14 kilometers from home to help his father harvest plantains, yucca and potatoes as a source of income. His dream is to become a lawyer so he can help people achieve justice and peace, but the law won’t allow it. When he returned home one day after work, he laid down in the middle of the concrete floor next to the worn and feeble dining set. He stayed like that, staring at nothing, for a long time as if he was stuck, knowing he’s destined to follow his father’s footsteps in the plantation fields.

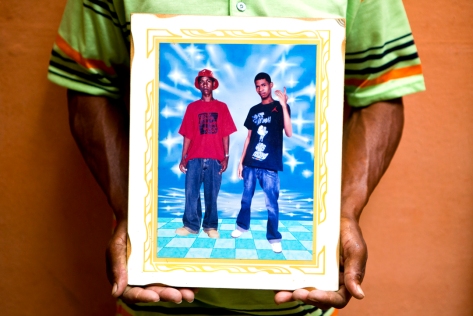

Last July, Miguel was signed to the Toronto Blue Jays. Come October 2014, he will leave all he has ever known to play in the minor leagues in Florida.

Last July, Miguel was signed to the Toronto Blue Jays. Come October 2014, he will leave all he has ever known to play in the minor leagues in Florida.